For my second capstone project at UBC, I had the absolute pleasure of working with Dr. Hal Clark of BC Cancer Agency in order to develop methods for medical image registration to enhance cancer treatment plans. You can find his website here.

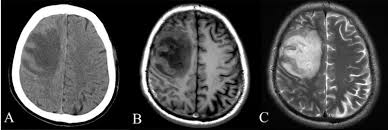

The main problem that we wanted to address is obtaining useful scans for cancer treatment. Patients generally obtain CT scans for coming up with a treatment plan and tracking progress but recently there has been more of a push towards using MRI scans as well in order to obtain better resolution of body tissue. The issue is that it is hard to tell what features correspond to each other when looking each scan, even though they are showing the same thing!

As you can see from the comparison image, a lesion which is very broad in the CT scan of A is much more defined in image C. Additionally, while the skull in A is very well defined, it is tough to determine where it is exactly in either B or C.

You might think, “why not just take the best image and use that?”. However, it is hard to decide which is the best image precisely for the reasons above. If only there was a way to get the best features from each image into a single “master image”. Well that is precisely what image registration is made for!

Image registration is the process whereby one can morph one image to match another thereby registering the images to one another. From here, a simple overlay of the two images will allow you to see the best features from both images in one. This is what our team set out to do.

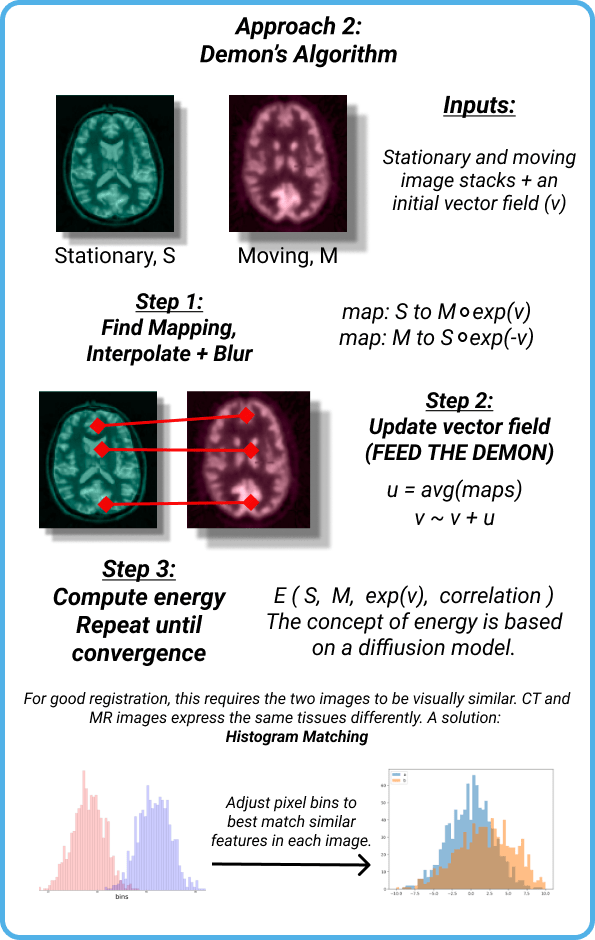

Our research led to many different algorithms with some promising potential. The one that I investigated is called “Demon’s Algorithm”. Here is the poster page that I came up with to explain the approach:

I heavily simplified the process to three main steps:

- Find a mapping between the two images using some MATH, this can be represented by a vector field.

- Keep track of this vector field (I think this is called feeding the demon, although I don’t know that for sure 🙂

- Compute an energy for the system using MATH and repeat all of this until your energy eventually converges to a minimum.

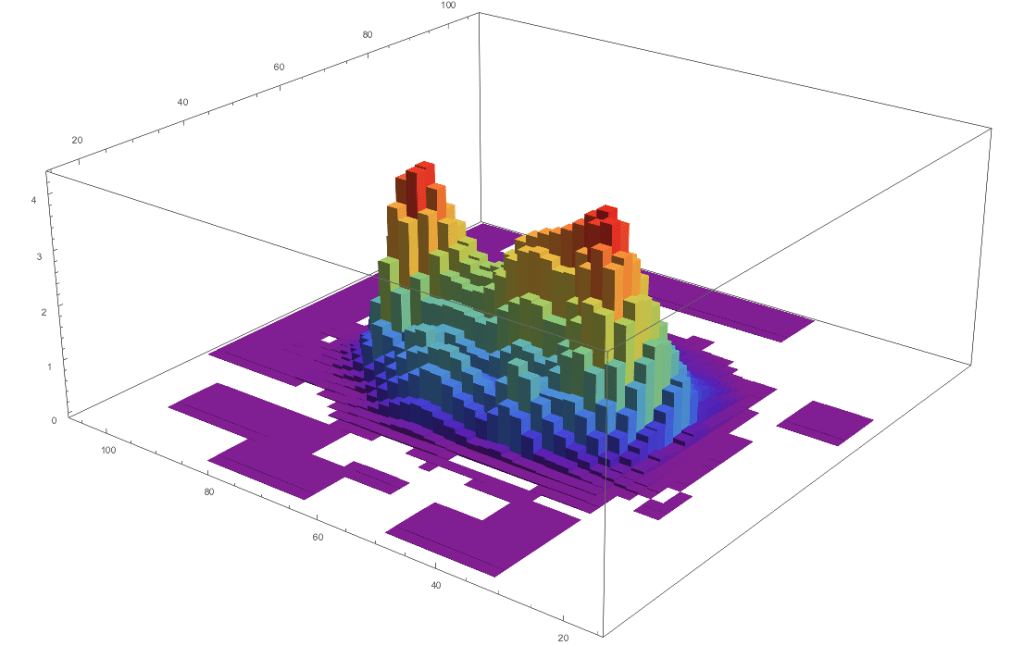

The whole model is based on the process of diffusion. What I would imagine while working on this is a 3d mapping of pixel brightness forming these strange shapes as below:

Treat one image as a solid and the other image as a sheet, then simply imagine the sheet falling atop the solid and slowly shifting and changing to match the shape of the solid. MATH is cool.

One of the major issues with using Demon’s algorithm, however, is that we will not be able to achieve that CT-MRI registration that we wanted. The pixel intensities of similar features in each image simply do not correlate so dropping an MRI sheet onto a CT solid produces some nonsensical results. This is why a step is needed before using Demon’s in which the pixels are normalized to each other. We investigated histogram matching for this step, but the results were pretty inconclusive. Better methods exist and definitely need to be implemented before implementing Demon’s algorithm but it is still useful to look at how the algorithm performs.

Here are the results that I found:

Registering a deformed image to a “normal” image

| FIXED IMAGE | MOVING IMAGE | DIFFERENCE |

| 50 iterations | 100 iterations | 500 iterations |

A quick note about what “Difference” means. Given each pixel in greyscale is a value from 0-255, “Difference” is just the absolute difference between the pixel values in the two images – so a solid colored “diff” image is ideal.

Registering a rotated image to a “normal” image

| FIXED IMAGE | MOVING IMAGE | DIFFERENCE |

| 50 iterations Time = 18 seconds | 100 iterations Time = 40 seconds | 500 iterations Time = 257 seconds |

From the results above it does seem that the algorithm can work on deformed images but not so well on simple rotation. However, there is a cool trick that we can do to help with this!

| WARPED IMAGE / DIFFERENCE 50 iterations, 6 levels = 300 iterations. Time = 41 seconds | WARPED IMAGE / DIFFERENCE 250 iterations, 3 levels = 750 total iterations Time = 192 seconds |

Here we used a method called downsampling. Essentially, we take the image and immediately turn each pixel into multiple pixels in a way that our original 200x250px image becomes something like 400x500px or 800x1000px. Performing Demon’s algorithm on this becomes lengthier on each iteration but each iteration also becomes much more efficient. We can see that by using 6 levels (6x the number of pixels per dimension) we achieve results after 50 iterations that are similar to the single level results after 500 iterations. Additionally, I found that it was very optimal to use 3 levels and good convergence was found after just 250 iterations.

These results are promising and some work can be done to make it even better.

- Adjusting the levels of each iteration to save computation time will be crucial. I performed tests on single 2D images, typical CT scans are actually very many 2D images in a stack to essentially form a 3D image. So minimizing this computation time for larger image sets will be crucial for performance.

- Processing the images beforehand to avoid rigid transformations like rotation/scaling could help significantly bring down the number of iterations needed for convergence. Simple affine transformation algorithms exist to help with this.

- I coded this in 2D so the equations will need to be extended to work in 3D.

Thanks for reading all the way to the end here, I’m glad that I was able to work on such a cool project, I certainly learned a lot about some cool ways physics is being used to treat cancer patients. I hope that I will be able to continue some work on this in the future, it would be very cool to get something working that will be able to save lives.