A lot of people have asked me how I learn/memorize things for school. However, learning and memorization are two very different things. I thought that it would be good to explain the power of each of these tools using cubing as an example.

I started speedcubing when I was in grade 11. It was part of a self-directed project for my programming class. My overall goal was to be able to solve the cube as fast as possible. Here is the map that I planned out to do this:

Understand the structure/process. Find out what methods there are and how each one works.

Learn the steps one at a time. Some will be intuitive and easy to understand, others require brute force memorization.

Practice until everything is committed to muscle memory.

With this strategy I went from knowing nothing about Rubik’s cubes to a 30 second solve in just 4 weeks. This includes learning tons of algorithms needed to solve it faster. Let’s go over each of these steps in more detail.

understanding

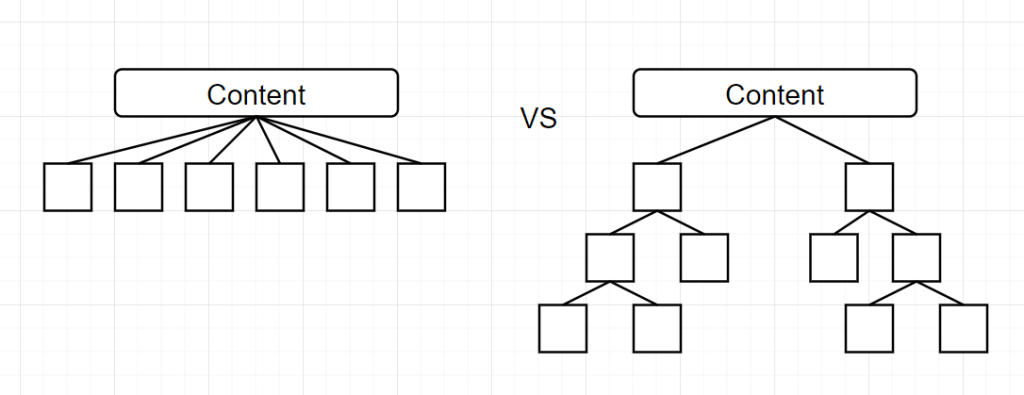

I find that when learning a new concept it is best to understand it at the highest possible level, looking at the concept as a whole rather than its individual parts. For the Rubik’s cube this means understanding that there are certain steps you take to solve the cube. The simplest method is going layer by layer. At this point you just want to understand this process and use it to guide you moving forward.

Applying this to learning a new concept, you want to ask the following questions:

How does this concept relate to what I know?

How can this concept be partitioned into different parts?

What is this purpose of this concept overall?

By asking these questions you build connections to this new concept with your preexisting knowledge. When we understand the structure of a concept in our mind, we form spaces for that concept to snap into place to fill in the gaps once we learn more. It’s like doing borders first on a jigsaw puzzle.

learn the steps

Once you have the mental map set in place, it is time to start working your way through it. For solving a Rubik’s cube, the first step is to do one layer. There is no specific way to do this, it is often easiest to just figure it out intuitively by playing around with the cube and exploring different patterns. The next couple of steps are not intuitive. In fact, the last two steps are pretty much pure memorization with no way around it.

This is similar to many concepts that you will have to learn at school. Sometimes concepts are just intuitive. You get them right away because they fit into your idea of how the world works. Other concepts (most concepts) will require some hardcore memorization to cram everything into your brain before test day.

what’s the best way to memorize lots of things

I learned 78 different algorithms for solving a Rubik’s cube in just ten days. So how did I do it? What’s the secret? The short, bad, and lazy answer is:

just practice.

I’m not a big fan of this answer, it doesn’t really describe what is truly going on. It also doesn’t define the difference between good and bad methods of practice. So I’ll try to dive deeper into this and explain how I really was able to memorize everything through five helpful tips!

tip 1: make a study sheet

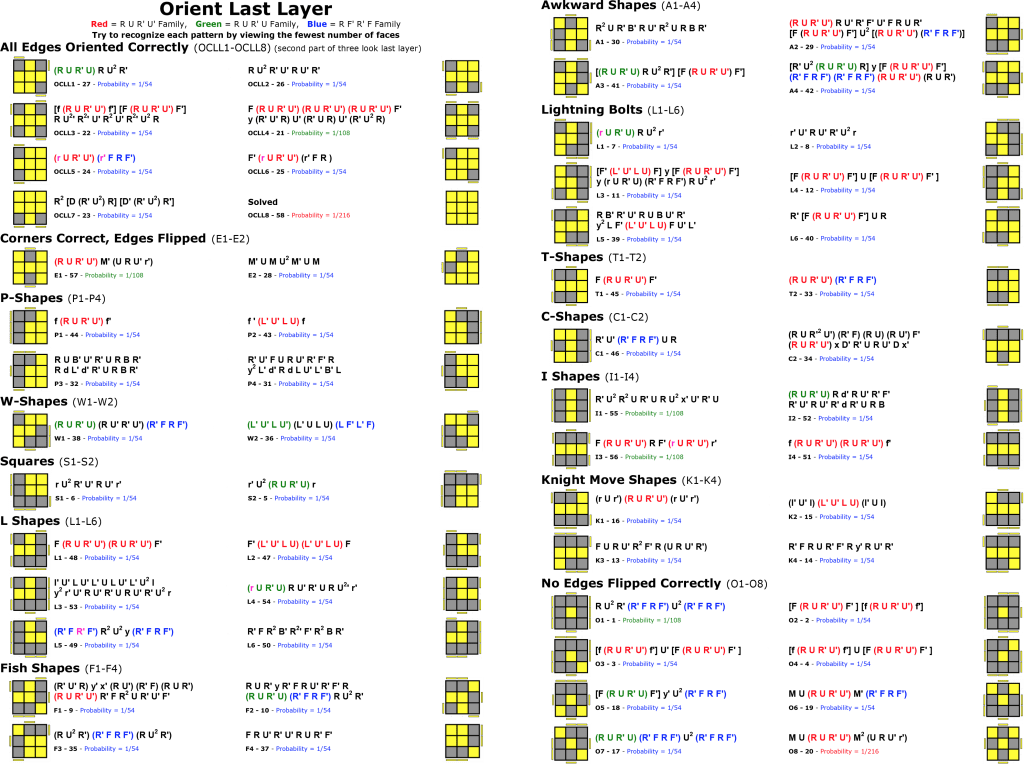

I was lucky enough that for speed cubing, there are tons of resources and study sheets that people have made and post on the internet. Like this one that I learned from:

There are some subtle things going on in this sheet that make it so much more powerful.

- First of all, recurring patterns are highlighted in different colours. By memorizing a single four-move sequence, you have less to memorize on other algorithms that use this sequence.

- Secondly, the content is organized into different subcategories. There are the very easy to learn P-shapes and then there are the terrible “No Edges Flipped Correctly” a.k.a “Dot” cases. By sub-grouping the content to memorize, you can recall it easier. You create a map in your mind with more groups.

- Finally, it’s just easy to read. I know that an issue for some is that their notes are too messy to read or they write a study sheet but all of the content is all over the place and disorganized. You end up wasting more time looking for information you wrote down rather than memorizing it. Use online software to take notes if it helps. A good resource that I use is draw.io. You can create text boxes and easily resize them and place them wherever you want on the document. You can add symbols and draw connections between items as well. You also don’t have to worry about formatting too much.

tip 2: move on, distract, then actively recall

The most useful practice that I did was to take a break from studying then after a couple of minutes I would try to recall everything that I could without looking at a cheat sheet. You quickly learn what you don’t know and what you know really well. Repeat the process several times until you find you are remembering everything.

I also use this strategy when studying for tests. After reviewing all of the material and making sure I understand how to do problems, I would take a break. Then I would put all my notes away and pull out a practice exam and work through it.

tip 3: activating your procedural memory/muscle memory

Your procedural memory (a.k.a muscle memory) is the part of your memory that remembers how to do things. You remember the walk from your house to school because you’ve walked that path so many times. This type of memory is much deeper and more powerful than explicit/descriptive memory.

When I was learning to cube, I began by reciting the moves in my head as I did them. I was using my descriptive memory to access the part of my brain that stored the information on the next move to make. After repeating the process dozens of times and getting a feel of the movements with my hands, the process became less descriptive and more of a reflex. Now I can perform 13 move algorithms in under 1 second. However, if you asked me to name every single move involved it would take quite a bit of thinking.

Procedural memory can also be used in answering test questions. When you make mnemonic devices or when you put a tune to a set of words, you are trying to use part of your procedural memory. You remember the order of the alphabet well but if someone asked for the 20th letter, you would most likely sing it and count with your fingers.

tip 4: be persistent

Usually deadlines will help with keeping you in check. However if you decide to learn how to speed cube and see that there are over 50 algorithms to remember just to get a few seconds faster, you will probably not be very motivated. After all, there is a lot of other areas to work on such as turning speed and look ahead, why do you need to learn every single case when you can just learn 10 or so and get by.

The thing is, even if there are other areas to improve, you will soon hit a wall where it will become increasingly difficult to improve without learning. This is true for almost anything. The easy path also becomes increasingly narrow. Putting in the work now will open up opportunities later on.

tip 5: have fun / don’t burn out

Not sleeping the night before an exam is usually detrimental to performance. Approaching any situation with a clear head is always ideal. Even if the exam is incredibly stressful and intimidating, you will be better off getting rest than staying up to study for the extra 7 or 8 hours.

In terms of cubing: it’s not school, it’s a hobby. Have fun with it. If you don’t want to learn algorithms today, don’t learn algorithms today. Just do some practice solves, work on other things, just enjoy whatever it is.